Highlights from “Not the End of the World”

Notes from a talk based on the book by data scientist Hannah Ritchie. You can’t do justice to it in a short talk so if you can, do read it. It covers a lot of subjects including air pollution, biodiversity loss, deforestation, plastic pollution, and over-fishing, but here are some of the most striking ideas. (Some of the graphs/data in the book are available online.)

How optimistic do you feel about the environment?

(on a scale of 0 = totally pessimistic, we’re doomed to 10 = sure it’ll be fine)

Humans used to live in harmony with nature, but not in the last 200 years. And our generation is destroying the environment faster than ever before. Nothing is being done and we are rapidly passing all tipping points, soon it will be too late.

This pretty much sums up the situation we’re in, right?

But it’s not really true.

So is it all fine, nothing too much to worry about?

That’s not true either!

Ten Surprises

But first, a common definition of sustainability: “Meeting the needs of the present without preventing future generations from meeting their own needs”.

When was the world sustainable? Pre-industrial revolution? Medieval times? Iron Age or neolithic times, early farming communities? Hunter-gatherer tribes?

Surprise #1: The world has never been sustainable

Since the beginning of their time on earth, humans have hunted animals to extinction. They have burned wood (then coal, gas, oil) – whenever anything is burned, air pollution (and greenhouse gases) result. Forests have been cut down since the earliest times.

Small communities such as indigenous peoples have sometimes achieved balance with the environment and other species – but only because they stayed small, and that’s because of child mortality. Half died before reaching adulthood. That’s not meeting the needs of the present so it isn’t sustainable.

First half of sustainability: meeting the needs of the present

Thinking about the whole world including the poorest countries: what percentage

- of children globally die before their 5th birthday?

- of people get enough to eat?

- of girls in low-income countries finish primary school?

Have a guess before reading on… here are some answers.

- 4% (compared to 43% in 1800)

- 13% (2013) – was 35% in 1970s. Even less now.

- 64% (2020)

Not as bad as you thought maybe? These are still not good, of course! – but we have to keep in mind that it’s possible for a things to be simultaneously: much improved, still not good enough, and able to improve further – true for many other aspects of sustainability too.

Surprise #2: Have made good progress on first half of “sustainability”

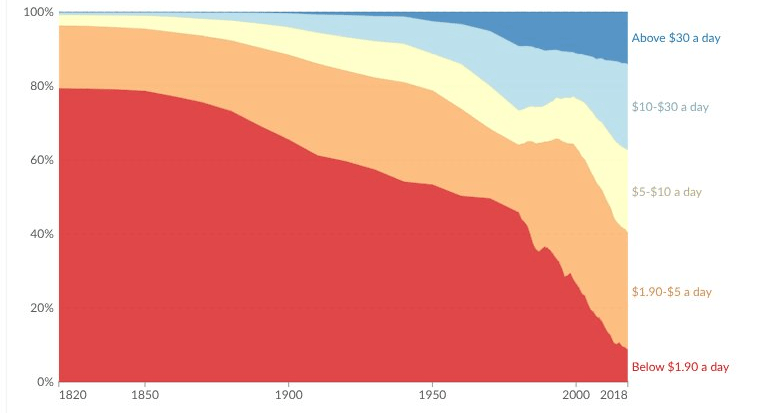

You can see from this graph, showing the percentage of the world population below various poverty thresholds, that there has been recent very good progress at reducing poverty (NB data adjusted for inflation and different prices in different countries.) “There has never been a better time to be alive.” This may come as a surprise to those who grew up in the Band Aid/Live Aid era! Good news doesn’t make the headlines, but there could have been a headline that “The number of people living in extreme poverty has reduced by 128,000 since yesterday” every day for the last 25 years.

Now let’s look at the second half of the sustainability definition. In lots of ways, we are preventing future generations from being able to enjoy and use the earth as we do. There are two fundamental reasons often given for this…

Surprise #3: Depopulation isn’t the solution

It’s often said the basic problem is there are too many people on the planet.

Population growth is not exponential – the rate of population growth peaked at 2% in 1960s, and has now more than halved to 0.8% in 2022 – more children survive but globally the number of children per mother is now less. (Often a side-effect of reduced poverty and better education.)

When do you think the number of children on the planet will peak?

It’s already happened. In 2017 there were more under-fives on the planet than there ever were or will be. Global population is projected to peak in the 2080s. (UN projections.)

More importantly, the goal is to reduce environmental impact per person to zero, or very close to zero, or even negative (reduce historical impacts). Then it doesn’t matter if it’s 7 billion or 10 billion people. A large number x zero is still zero.

Surprise #4: Degrowth isn’t the solution

A relentless focus on economic growth is also often blamed, because eicher people use more resources and have a higher environmental footprint. However as we’ll see, that’s not always true.

The first reason why degrowth isn’t a solution is that we need economic growth to end poverty, even with lots of redistribution.

Denmark is one of the most equal countries in the world. Nearly everyone lives above the $30 a day poverty level. For every country to be like Denmark, we need to grow the world economy five-fold.

For everyone to be on exactly $30 a day, the world economy would have to double. NB In 2018 70% of Europeans lived above $30 a day.

But there’s an even more striking reason!

Historically economic growth was linked with more resource intensive lifestyles – being richer meant people burned more fossil fuels, used more land, ate more meat, had a higher carbon footprint. But new technology means the environmental footprint reduces while continuing to get richer.

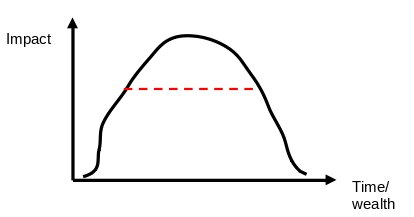

We often see this upside-down-U shaped graph. An example is air pollution – in the UK it got worse as we industrialised but is now much better than in the 1940s or 1880s (although still not as good as it needs to be.) We can decouple economic growth from environmental destruction.

However the graph shows it can get worse before it gets better – but wait, notice the red dotted shortcut line…

Developing your low-income country

It’s 2009 and you’re the prime minister of a low-income country and need to build a power plant. Here are the costs per unit of electricity:

- Solar PV: $359

- Onshore wind: $135

- Nuclear: $123

- Coal: $111

- Gas: $83

You want to prevent global warming, but you have which are you going to have to choose?

Now it’s 2019, and these are the costs per unit of electricity:

- Solar PV: $40

- Onshore wind: $41

- Nuclear: $155

- Coal: $109

- Gas: $56

In ten years it’s changed completely. Technology can shortcut the hump of the upside-down U.

Who lived more sustainably, you or your grandma?

You probably drive more, have a lot more gadgets to power, maybe take one or more aeroplane flights a year, buy more stuff, probably waste more food.

Surprise #5: you!

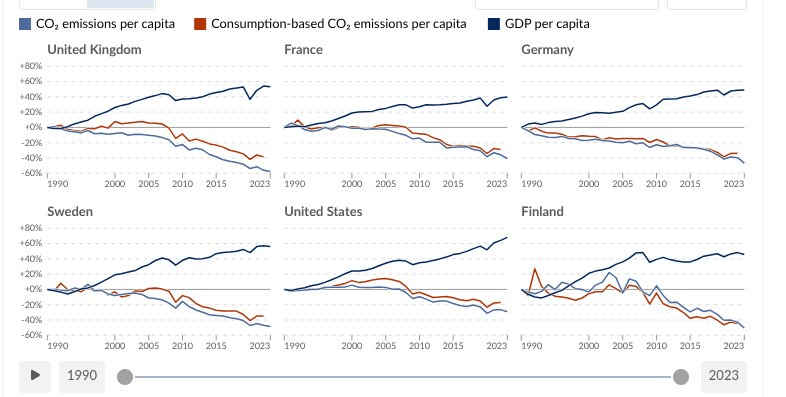

In 1965 the average person in the UK emitted 11.5 tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year. Now it’s 5 tonnes or less.

Why? Our energy supply then was almost entirely from coal. And cars, appliances etc have become more energy efficient.

But what about other countries? Eg the USA. In the last 15 years (which included the last Trump presidency) do you think per capita emissions have gone up by 20% or more, or by 10%, or stayed the same?

Per capita emissions in the USA have fallen by 20%. Similar for other developed economies – even if you take account of “offshoring” (ie even if you account for industrial production moving to eg China. That’s the “consumption-based emissions” red line in the graphs above.)

Global emissions per person peaked 2012. But there’s still a race between the rising number of people and falling per person emissions. They aren’t falling fast enough but this shows it’s possible they can – it’s already on the right track.

Focus on food…

Because food on its own uses three times the total 1.5° carbon “budget”, it’s a leading cause of deforestation, and of biodiversity loss (through land use.) But we need all that to feed the world… or do we?

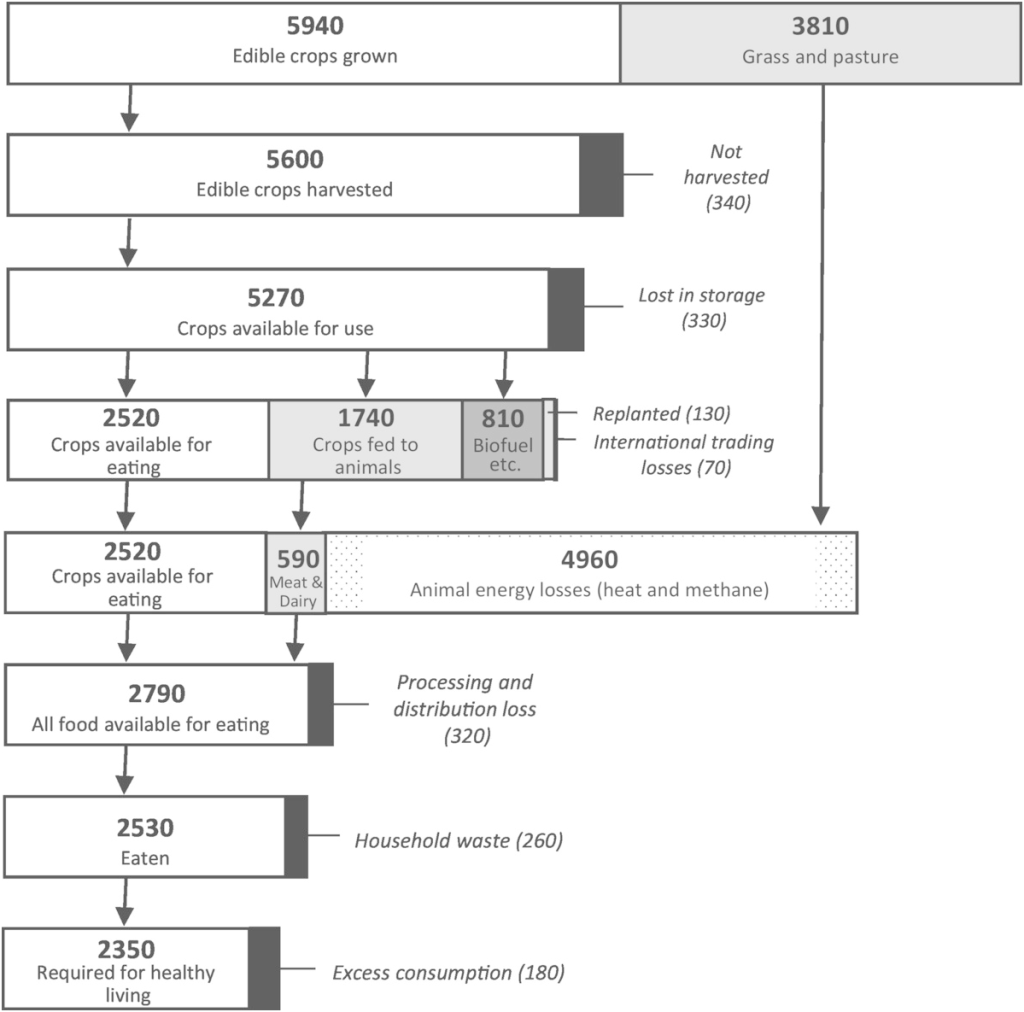

Surprise #6: the world produces twice as much food as it needs

The average person needs 2000-2500 calories. But if we were to split the world’s food production equally among the world’s population, each person would get 5000 calories! Why?

The main reasons are growing crops to feed livestock is a very inefficient use of food; food grown as biofuels; also waste and over-consumption. If we used less land to grow food, more land would be available for wildlife.

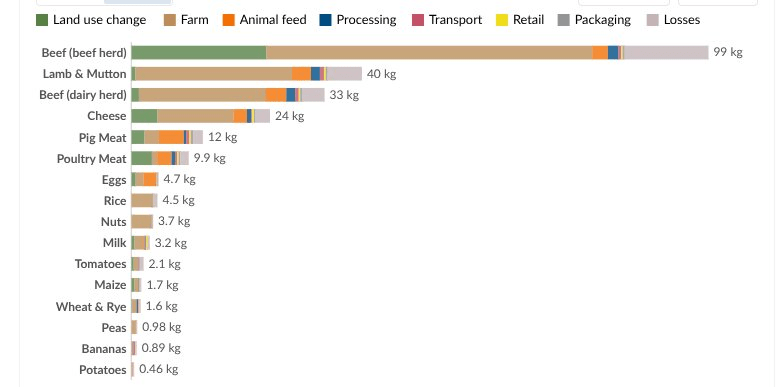

You can see from the above that beef is particularly bad for the climate (and deforestation) but following that are other meat and dairy products.

Uncomfortable surprises #7

Here were some conclusions about food that challenged my presumptions:

- Cheese is as bad as meat

- Transport is a small part of the carbon footprint. “Eat local” less important to think about than “Eat seasonal”?

- Packaging is a small part of the carbon footprint

- Is it better to reduce the total land taken for food growing with careful fertiliser use than to go organic everywhere?

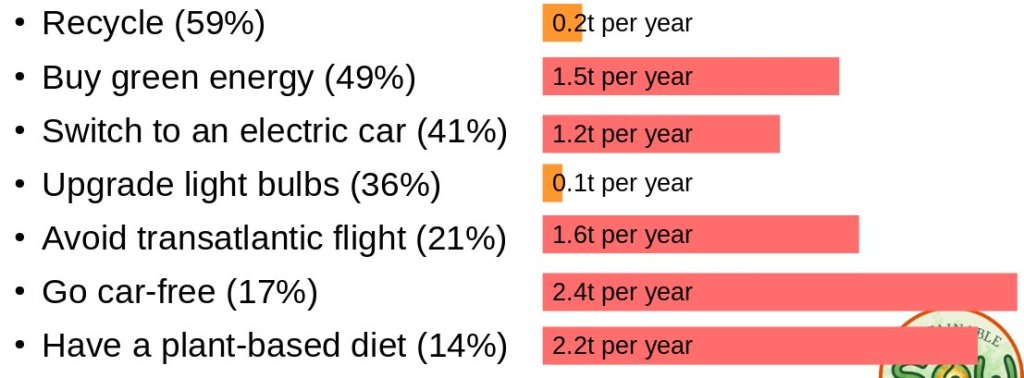

Surprise #8: The most effective ways to cut our carbon footprints often isn’t what people think they are

21,000 adults across 30 countries were asked what are the most effective actions. Here are their answers compared to the tonnes of CO2-equivalent typically saved per year by doing them.

The problem isn’t that we do the lower-impact actions, it’s when we do them instead of the higher-impact ones – or stress over the little things.

Is change possible?

Last two questions to ponder over!

- In Covid, when everything around the world shut down, how much did global CO2 emissions fall by?

- Name the first international convention to be ratified by every country in the world

Here are the answers:

- 5% … that’s all the difference that almost all of us not driving, not consuming, etc made. Discouraging? But…

- The answer is the the Montreal Protocol (1987) – every country had signed up by 2009 …

Surprise #9: Systemic change is necessary AND possible

Remember the Montreal Protocol? It was to phase out ozone depleting gases. The hole in the ozone layer and acid rain were two big environmental issues of the 1980s. Now that CFCs are no longer used, the ozone hole is closing up and in due course won’t be a problem any more. Acid rain has likewise almost disappeared across N America & Europe. Even in China sulphur dioxide emissions have fallen by two-thirds while coal use doubled in the last decade.

It shows that if we have a technical solution to a problem, and political will and investment, then we can act very quickly to change at a system level.

Summary of surprises

- Environmental damage is not a recent thing – don’t hark back to a perfect (all-natural) past

- You don’t always hear about the good news

- You can’t just blame too many babies

- Sustainability can (and in practice does eventually or sooner) increase with GDP

- “More sustainable than Grandma” – progress is happening, not quickly enough but it is happening

- We could feed the world with less land. Food is an example of how environmental problems are interconnected – means one solution can solve several problems at once

- My environmentally friendly instincts may be misguided or out of date (eat local etc)

- Don’t have to worry equally about everything we do. Some things matter more than others

- High level change is needed – and is possible, it’s already happened

Surprise #10: We aren’t the generation which messed it up…

… we’re the first generation with a chance to fix it

How optimistic do you feel about the environment now?

Pingback: SOW Updates & Plans | Sustainable Oakington and Westwick